|

|||||||||||||

|

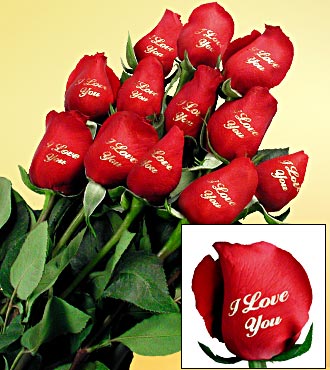

Blossom Florist’s Flower Delivery in Minnesota is the greatest. Our Minnesota Flower Shops offer flower delivery in Minnesota with a 100% satisfaction guarantee. Our goal is to send only fresh flowers to Minnesota with our professional and caring staff that is always available to serve your needs.

|

|

Minnesota Click here to Send Flowers to Minnesota Today |

||

|

Minneapolis, MN |

Saint Paul, MN |

|

|

Our General State History and Information

Humans first came to Minnesota during the last ice age, following herds of large game as glaciers melted. Long before the first Europeans arrived, Indians from as far away as 1,000 miles came to make ceremonial pipes from soft read pipestone carved from sacred quarries. The Pipestone National Monument in southwest Minnesota illustrates how these quarries were and still are used.

Five thousand years ago, humans made rock carvings of people, animals, and weapons that can be seen today at Jeffers Petroglyphs in southwest Minnesota. These people also brought to Minnesota the idea of building earth mounds for graves and sacred ceremonies. At one time, there were more than 10,000 of these mounds in Minnesota. When the first French fur traders, or voyageurs, arrived in the late 1600s, the Dakota (or Sioux) people had lived in Minnesota for many years. They hunted buffalo, fished, planted corn, beans, and squash, and harvested northern beds of wild rice. They lived in warm skin tipis in the winter and had airy bark houses, or wigwams, for the summer. The Anishinabe (or Ojibwe, also Chippewa) people moved into Minnesota from the east. They lived much like the Dakota, but from the French fur traders they obtained metal tools and weapons, cloth, blankets, and ornaments. By 1800, the Anishinabe had taken over the lakes and woods of the north. In the early 1800s, the U.S. government said it needed more land in this area. The Dakota signed a treaty with the U.S. government for the land where the Minnesota River joins the Mississippi, and, in the 1820s, Fort Snelling was built there. During the years that followed, the Dakota and Anishinabe tribes were forced to sign treaties to relinquish most of Minnesota to the U.S. government. Thousands of new people poured into the region to build farms and cut timber. In 1858, Minnesota became the 32nd state. THE DAKOTA CONFLICT By 1862, the Dakota were crowded into a small reservation along the Minnesota River. Times were had and Indian families hungry. When the U.S. government broke its promises, some of the Dakota went to war against the white farmers and towns. Many Dakota did not join in, but the fighting lasted six weeks and many people on both sides were killed or fled Minnesota. Afterwards the government forced most of the remaining Dakota to leave Minnesota. The Anishinabe stayed in northern Minnesota, and were not involved in the war. Our Historic Figure James J. Hill 1838–1916: He was called the "Empire Builder." He was a powerful business leader; builder and owner of the Great Northern Railroad, Great Lakes steamships, Coal mines and iron mines.

Chief Little Crow 1820-63: Chief Little Crow was the eldest son of Cetanwakuwa (Charging Hawk). It was on account of his father’s name, mistranslated Crow, that he was called by the whites "Little Crow." His real name was Taoyateduta, His Red People. He was a leader in the 1862 Sioux Uprising.

|

||

Birthday |

Valentine's Day |

Christmas |

Mother's Day |

Father's Day |

We specialize in wedding | New Baby and Symphaty / funeral flowers.

Link Page

We specialize in wedding | New Baby and Symphaty / funeral flowers.

Link Page